Every novel has a backstory arising from the author’s experience, imagination and research. Because there are several plot threads in Temple Dancer, there are at least three backstories. In this 3-part series, I’ll review the backstory that led to the emergence of Saraswati as a character in an Indian village in 1938.

Reaching Out

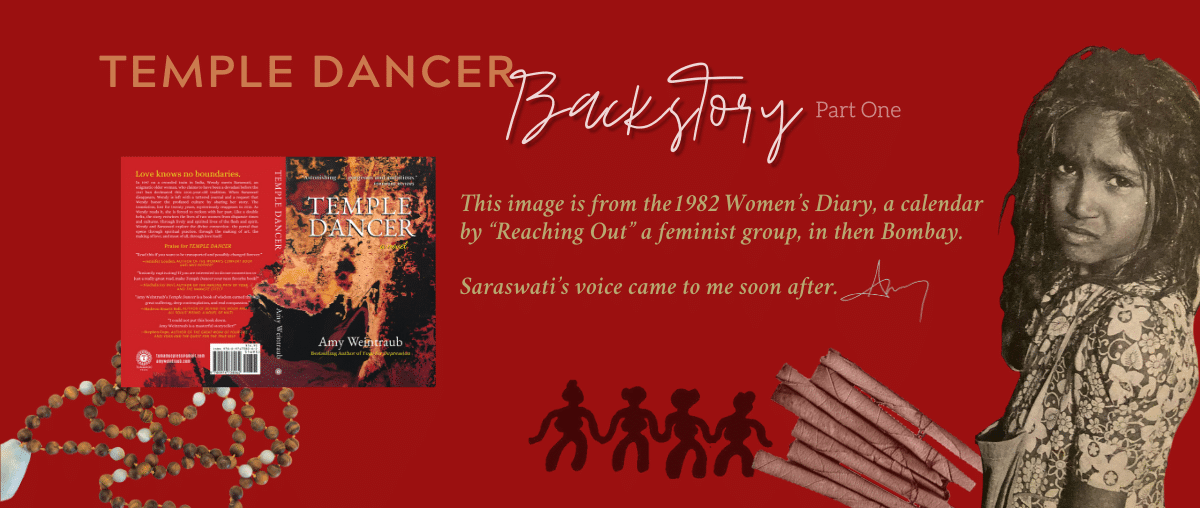

On the day I stood in C. S. Lakshmi’s office in Mumbai, looking at a calendar created by “Reaching Out,” a group of Indian feminists, my eyes locked on the eyes of a little girl who gazed into the camera. Rohini stood holding her mother’s hand. She was six. She had knotted hair. Her mother said that she was going to be dedicated the coming year. Rohini stood silently. Stunned and momentarily breathless, tears welled with the knowledge of what “dedicated” meant, of what this beautiful child was destined to become.

This moment occurred while traveling in India in 1994. I was visiting the award-winning author Ambai (the pen name for C. S. Lakshmi, academic and feminist). I had contacted her after falling in love with her collection of short stories, A Purple Sea, on a trip to India the previous year. Lakshmi showed me the calendar that she and her colleagues had created in 1982, to raise awareness of the plight of poor female beedi rollers in the Indian state of Karnataka. Because of their exposure to tobacco in unventilated spaces, the beedi rollers often developed lung diseases, including tuberculosis.

Temple carving

Yellamma

Many of these women were dedicated to the Goddess Yellamma, the patron saint of poor women, often of a lower caste. What this meant in 1982, and continues to mean, was that the young girls’ families were committing them to a life of prostitution, often to help the family survive. Temple dancers were outlawed in 1947, and dedications to Yellamma have been banned since 1934. Those dedicated since then, are not dancers. They often become sex workers. Accompanying another picture in the calendar is this: Sangeetha here is 12 years old. When the first knot in her hair was cut off, she became sick. Her father died. Then it was decided to dedicate her. “I will be happy,” Sangeetha said smiling, not knowing the implications of dedication. Every year thousands of young girls are taken to the Yellamma Temple in Saundatti, a village in Karnataka, to be dedicated to her.

Saraswati

When I returned to New England, the impact of meeting six-year-old Rohini’s gaze stayed with me. Several weeks after my return, the voice of Saraswati began to pour through me. I had been writing fiction before, contemporary stories about love and work, but I have never had an experience like this one before or since. It was as if her voice found me and used me as a vehicle to tell the story of the devadasis.

Part Two is here.